In a century marked by wars, consumerism, and technological acceleration, Buckminster Fuller (1895–1983) dared to ask a radical question: what if humanity could prosper without destroying the planet? For him, it wasn’t a naïve utopia but a design challenge. He believed that, with ingenuity and cooperation, we could “do more with less” and secure abundance for everyone.

Design as a political act

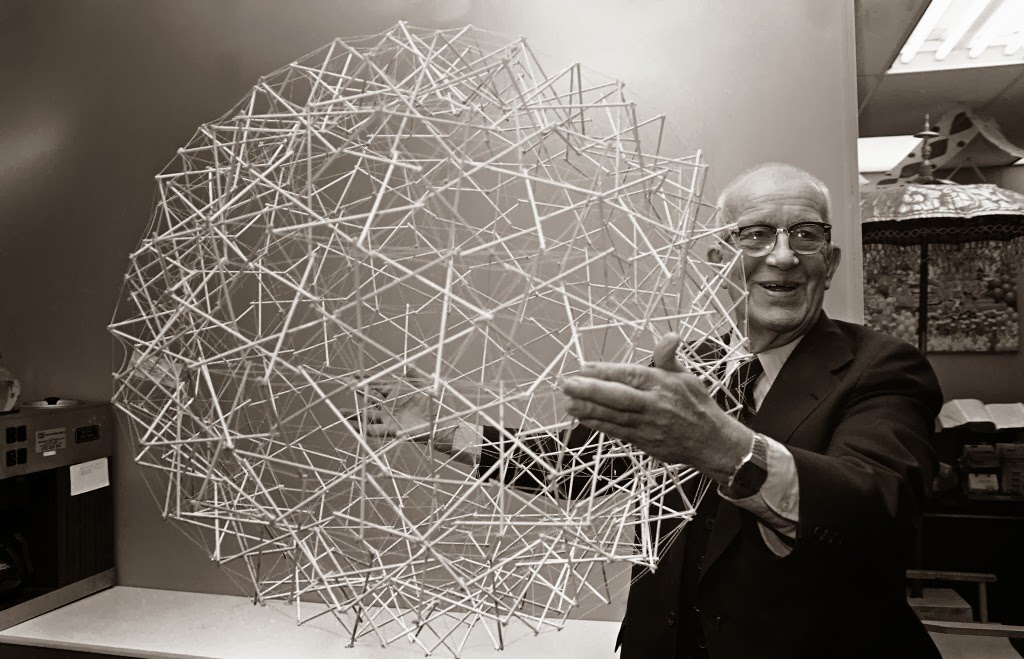

Fuller was never a conventional academic or a typical businessman. His projects often looked like something out of a science fiction novel, yet they all shared the same purpose: rethinking the relationship between resources, technology, and human well-being.

The geodesic dome is a prime example. More than a structural experiment, it became a symbol of sustainable architecture: lightweight, affordable, and resilient, with applications ranging from housing in vulnerable areas to bases in extreme climates. It remains a timeless icon of ecological innovation.

Another milestone was the Dymaxion House, a circular, prefabricated, and energy-efficient prototype. Designed to be mass-produced and shipped like an appliance, it never reached scale but anticipated today’s modular and self-sufficient homes—solutions now resurfacing in response to the climate crisis.

Even his Dymaxion Car, an aerodynamic three-wheeled vehicle from the 1930s, showed how far ahead he was: efficient use of resources, compact design, and urban mobility. Decades before discussions about electric cars or sustainable cities, Fuller was already testing, imagining, and prototyping.

The metaphor of Spaceship Earth

Perhaps his greatest contribution was not material but conceptual. Fuller coined the metaphor of Spaceship Earth. We are all passengers on this ship, interdependent, with limited resources and no manual. For him, the true politics of the future had to be the engineering of care: how we manage energy, food, and materials so that no one is left behind.

His vision challenged the logic of scarcity and conflict. He didn’t see the planet as a zero-sum battlefield but as a regenerative system where design could multiply collective benefits. In other words, the goal was not to distribute poverty but to create abundance through responsible innovation.

A legacy of intellectual courage

Fuller was not fully understood during his lifetime. Many of his inventions remained prototypes, and he was often dismissed as eccentric. Yet his intellectual courage opened new paths. Architects like Norman Foster, movements in ecological architecture, and even corporate sustainability theories draw inspiration from his work.

Today, as humanity faces climate crisis, inequality, and resource depletion, his ideas echo with renewed urgency. Fuller reminds us that it is not enough to manage what already exists—we need to reimagine it.

Looking at Buckminster Fuller means remembering that the future is not inherited; it is designed. His life teaches us not to accept limitations as destiny but to reinterpret them as challenges for creativity. He was, in essence, an architect of possibilities.

A visionary spirit for today

In times dominated by short-term thinking and fear, reclaiming that visionary spirit is more necessary than ever. Being a visionary today doesn’t mean fantasizing but daring to build real alternatives to the crises we face. As Fuller often emphasized, we already have the technology and material resources for every passenger of Spaceship Earth to live with dignity.

What we lack is not capacity, but imagination and will. That is perhaps Buckminster Fuller’s most relevant lesson: to dare to dream differently is not naïve, it is an act of responsibility. Only those who look beyond the obvious can open paths toward a better world.

“You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.”